The history of gang culture in America:

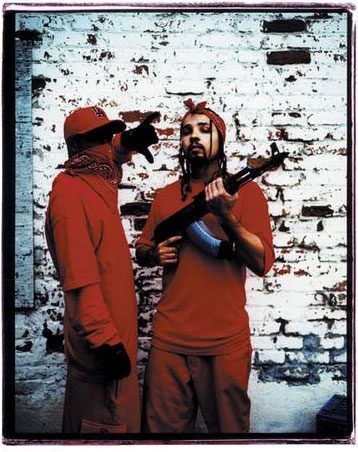

A four pages article for the ‘Red’ issue of WAD magazine.

The great photographer Estevan Oriol liked it and gave me some of his photo to illustrate it!

Learn more about the history of gang culture in the USA.

Do you know how the battle between the Crips and The Bloods first started?

We could hardly deal with the theme of ‘Red’ in urban culture without going to Los Angeles. It may be the City of Angels and all possibilities, but Los Angeles is also the cradle of gang culture and bloody shoot-outs. You know the cliché: the Bloods dressed in red protect their neighbourhood and head off around town to find some Crips to gun down. But behind the bandanas and clinking bling-bling hides a social phenomenon that finds its origins in the very roots of American culture.

HOW DID THE GANG CULTURE START?

“NIGGA QUIT LYIN’, YOU’S A NIGGA FOR LIFE” – SNOOP DOGG

The story began in the 1920s when less than scrupulous landlords invented racial restrictions aimed at stopping African-Americans from living in Los Angeles’ traditionally white neighbourhoods. With the help of some reactionary laws, the landlords stopped all possibility of different communities mixing, and contributed to the reinforcement of a ghetto feeling among the population. Over the years, this segregation established until, by the 1940s, it was a social reality. Racial conflict grew at the same speed as the growth of the ghettos on the east of the city and with more and more people arriving, the neighbourhoods (whose geographic limits were strictly contained) were soon overcrowded. Despite this, the white community continued its firm, overtly racist stance on territorial claims and continued its opposition to the creation of new mixed-race neighbourhoods. The feelings of hate and fear grew to the point that the Ku Klux Klan, which had all but disappeared 20 years earlier, was reborn. Some of the young white population banded together to create “street groups”, small groups whose stated aim was to fight any attempt at integration. Spook Hunters, for example, was a genuine neo-fascist militia beating up blacks who dared to adventure out beyond the perimeters of their allotted urban space. In reaction to this persecution, the first black street groups appeared with names like Devil Hunters, dedicated to protecting themselves from attacks. As black groups sprang up, the white population gradually began to leave the centre of the city, attracted by the expansion of the new suburbs. The neighbourhoods of Watts, Central Avenue and West Adams emptied out and became the cradle of new African-American gangs.

The 1960s saw the first black-on-black conflict. Black groups from different parts of Los Angeles began to face each other down under the cover of claims to different territory. The brawls between eastern and western neighbourhoods became common; the fights were mainly hand-to-hand (even if knives were used occasionally) and murders were rare. The main aim was each neighbourhood gang’s desire to prove to the other group the supremacy of its neighbourhood, while winning the respect of the old-timers.

POLICE ABUSES:

“I BRING CHAOS TO BLOCKS LIKE THE RIOTS IN WATTS” – METHOD MAN

Overcrowding wasn’t the only reason for the overriding feelings of distress. The misery of daily life was added to by an oppressive police presence. Police brutality insidiously reinforced the social pressure and feelings of persecution already growing within the population. The tension was already at a peak when in 1965 the violent arrest of a black driver lit the touch paper… and Watts exploded. The ensuing rebellion and series of violent riots lasted a week, with around 10,000 people taking part in the protest movement. The police were only able to restore order after 34 people had been killed and over 1,000 wounded. Yet it was in the ashes of this social upheaval that the consciences of a people in crisis were awoken. Influenced by the ideology of the Black Panthers and the US Organization, street gangs became radically politicized. The initial aim of the gangs, which over time had become blurred, was brought sharply back into focus through the spreading neo-Marxist message of Black Nationalist militants. Up until that moment, the battle had been a physical one (a defence of the neighbourhood from attack), but post-Watts it became a political battle to defend the neighbourhoods from the attempts at government subjugation. When black extremist organizations threatened to become some of the most important socio-political forces in the country, the police and the government began its attempts to thwart their irresistible rise. The powers-that-be created new paramilitary units (SWAT teams) to combat more efficiently any risk of future riots. The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover ordered his agents to try all possible methods to create splits between the different parties. The FBI and CIA reproduced the plan dreamed up to fight Communism: set up a propaganda campaign portraying the political movement as ‘dangerous’ for the general population. This witch-hunt kindled divisions between the Black Panthers and the US Organization, the two main parties. By the early 1970s, the murder of one of the leaders of the Black Panthers, blamed by the police on the US Organization, can be seen as the beginning of the end of black political groups’ influence in Los Angeles.

Photo by Estevan Oriol

BABY CRIBS & PIRU STREET BOYS:

“I SEE BLOODS AND CRIPS RUNNIN’ UP THE HILL” – 2PAC

The end of the 1960s saw the arrival of a new generation, one that had witnessed the height of the Black Panthers’ power and then watched in silence as it agonisingly collapsed. A whole generation marked by people they saw as social role models. They may have been too young to have taken in the political message, but they remained heavily influenced by the movement’s spirit of protest and fascinated by the party’s dress codes. And it was this attraction to the Panthers’ famous black leather jackets that was at the origin of the creation of the biggest gang in history. In 1969, Raymond Washington, a 15-year-old school kid, gathered together a few of his neighbourhood friends and founded the Baby Avenues, also known as the Baby Cribs. The gang’s original idea was to keep the revolutionary message alive and to protect the neighbourhood’s residents, but their interest quickly turned to more illicit activities. A look was central to the group and its identification with the Black Panthers pushed the members to sport black leather jackets. The gang dedicated itself to looking out for the famous jackets, attacking anyone wearing one and then stealing it. These attacks marked a turning point in Los Angeles’ criminal history when gangs went from fighting themselves to attacking the general population. The media were quick to jump on the gang’s criminal activities, in the process creating a certain aura that had an impact on the city’s young population. There has never been a clear explanation of the Crips name but one is that a local newspaper’s wrote Crips instead of Cribs and the typo stuck. Whatever the reason, from 1972 the gang became known as the Crips. The gang’s image was developed and honed. Between robberies and break-ins, the members paraded around in their jackets, carrying walking sticks and wearing earrings in their right ears. The ‘uniform’, aimed at bringing together the increasing membership, was then borrowed by various political/Mafia-like gangs in Chicago (such as the Disciples and Folk Nation). The increasing violence continued and it didn’t take long for the first murder to be committed: a 16 year old beaten to death for his leather jacket. The media coverage of the event did nothing to dissuade people from joining the Crips or creating their own gang. The phenomenon spread like wildfire, giving a population that had so often been marginalized a way of taking centre stage and finding an identity. At the end of 1972, there were more than 20 gangs and no fewer than 30 murders had been attributed to them. Due to their numerical superiority, the Crips terrorized the other gangs without fear of retribution. The Piru Street Boys decided to unite a number of gangs to create a solid anti-Crips union and protect themselves from the constant intimidation. The Bloods was born and the battle could begin.

CRIPS VERSUS BLOODS:

“GO BACK IN THE DAY, BRITISH KNIGHTS AND GOLD CHAINS” – MISSY ELLIOT

As time went by, the clothing rules of the two sides were established. They allowed the two gangs to affirm their unity and played a major role in the construction of their identity. In opposition to the Crips, who adopted the colour blue and wore their accessories on their right side, the Bloods dressed in red and wore their earrings and jewellery on the left. In prison, where uniforms made colour recognition impossible, members pulled up the trouser leg on the side that matched their gang affiliation. This practice was adopted in the street and even took in baseball caps (the peak was either worn turned to the left or right). The English brand British Knights saw its sales figures explode when the Crips decided to adopt its shoes, less for their looks than the significance of the logo: BK suddenly stood for Blood Killers. The Bloods responded by choosing Calvin Klein with the CK logo standing for Crips Killers. Affiliated with Chicago’s Muslim-influenced Almighty Black P. Stone Nation, the Bloods kept that group’s religious imagery and used the five-pointed star of Islam as their emblem. Over time, the red and blue colours were integrated into the tiniest details: bracelets, fat laces, socks, belts, rings, badges, bandannas, and so on. Some members even went as far as dying the inside of their pockets, which could be easily hidden should the police roll up. The two sides also wore Dickies and Ben Davis khakis, as well as flannel Pendleton shirts.

GANG CULTURE TODAY:

“GANGSTA, GANGSTA! THAT’S WHAT THEY’RE YELLIN'” – NWA

The foundations for modern gangs were laid in the 1980s. As an omen of the escalating violence that was soon to arrive, Raymond Washington, the Crips’ founder, was assassinated in 1979. From that moment on, no fight between the gangs could be settled without a bloody shoot-out. Gang territory moved out of its original inner-city ghettos, first across Los Angeles, then into many of the US’s larger cities. The savagery also grew exponentially and between 1980 and 1995, Los Angeles saw the creation of 150 new gangs, for the most part affiliated with either the Bloods or the Crips. The epidemic continues to spread to this day, reinforced by the catalysts of a number of cultural and social phenomena. Over the last 25 years, unemployment has continued to rise, generating in an already fragilized population a sense of bitterness and despair that sees no possible way out of its lack of prospects. In a more insidious way, cinema and music have contributed to spread the movement’s seductive image. The success in the early 1990s of gangsta rap and films such as ‘Boyz n the Hood’ and ‘Menace II Society’ (even if these films are far from rallying calls to the gangs) contributed to the popularization of the image of the gangsta in American society.

Today, the situation seems to be delicately balanced. With 400 gangs and around 50,000 members, the future of Los Angeles could be bloody. For the moment, while the number of gang members continues to rise, the murder rate has stabilized. The gangs’ aspirations for revolutionary change seem to have been definitively consigned to the past and it can be seen as a shame that the ghetto imagery has too often overshadowed political ideals. The gangsta has become a representation of a spectacular side of American folklore. The gangsta is now an icon, but one whose image is more useful in oiling the wheels of capitalism than fighting the problems of segregation and poverty that brought it into existence in the first place.